Invisible Scars: The Unseen Impact of Narcissistic Parenting on the Nervous System

Published on:

One prevalent theme I often hear among scapegoated survivors of dysfunctional family systems is the belief that something is inherently wrong with them. This internal dialogue often triggers a spiral of self-hatred, self-blame, and toxic guilt.

I myself deeply held this belief for the majority of my life, only becoming aware of its falsehood when I finally began to focus on learning to reconnect with myself and understanding how my nervous system has been shaped by my upbringing.

Survivors of toxic or narcissistic parenting do not face behavioral challenges in adulthood for “mysterious reasons.”

These struggles have nothing to do with ‘inherent badness,’ ‘flaws,’ or ‘a deficient character’; rather, they are closely tied how their nervous system has adapted to respond to their environment, essentially constituting trauma.

The Influence of Unpredictable Upbringings on Neurobiological Development

Children reared in environments marked by inconsistency or critical caregivers often face distinct challenges. Such settings can be characterized by unpredictability, where tension or conflict can emerge without warning.

This unpredictability can trigger a heightened state of arousal within the nervous system, leading to persistent stress responses.

In response to this chronic stress, some individuals may become entrenched in a “fight-or-flight” mode. In this state, the body remains on high alert, primed to either confront a perceived threat or flee from it. Conversely, others may develop emotional detachment as a coping mechanism, effectively numbing themselves to mitigate the discomfort and unpredictability of their environment.

The Autonomic Nervous System’s Arousal States and Trauma

The autonomic nervous system has two main branches: the sympathetic nervous system and the dorsal vagal system (a branch of the parasympathetic nervous system). These branches work together to regulate our body’s functions in response to perceived threats.

There are two main states of arousal within this system:

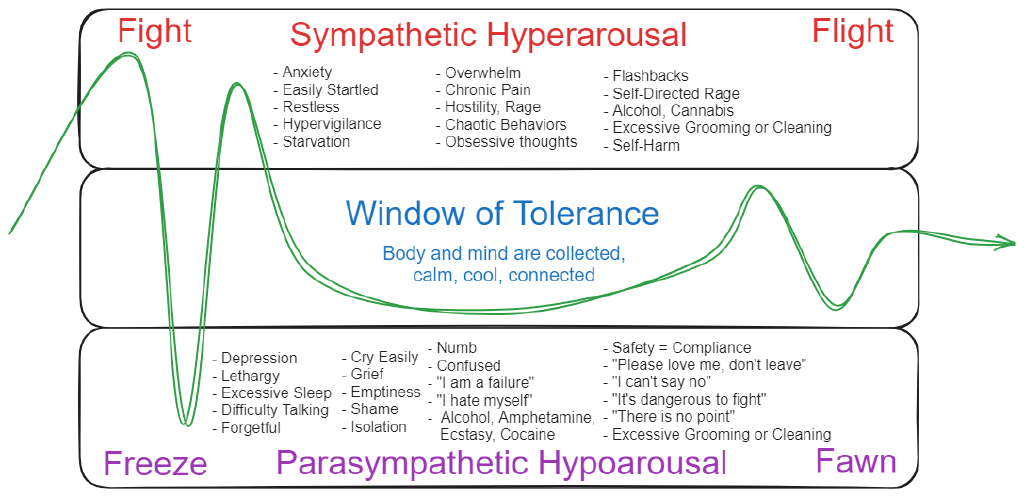

- Hyperarousal: This state is triggered by the sympathetic nervous system and is often referred to as the “fight-or-flight” response. During hyperarousal, the body prepares for action, increasing heart rate, respiration, and blood pressure. We may experience heightened alertness, anxiety, and difficulty relaxing.

- Hypoarousal: This state, sometimes called “shutdown,” is associated with the dorsal vagal system. In hypoarousal, the body conserves energy and prioritizes survival. This can manifest as feelings of detachment, dissociation, fatigue, and difficulty concentrating.

The Link Between Trauma and Arousal Dysregulation:

Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (C-PTSD) can disrupt healthy nervous system regulation, making it difficult to shift between hyperarousal and hypoarousal states. This can lead to:

- Chronic stress: Getting stuck in a hyperarousal state can leave us constantly feeling on edge and unable to relax.

- Difficulty processing stress: When faced with challenges, an overly reactive or under-reactive nervous system can make it hard to cope effectively.

- Increased vulnerability to re-traumatization: A dysregulated nervous system can make us more susceptible to feeling overwhelmed by stressful situations.

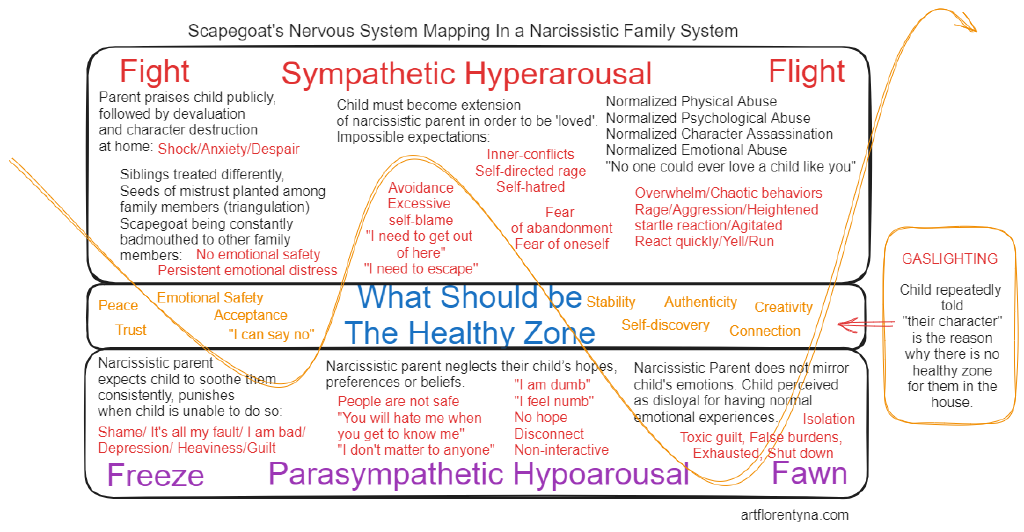

Fight-Flight-Freeze-Fawn: Trauma Responses to Abusive Family Dynamics

Experiencing narcissistic abuse from a parent, caretaker, or family system can profoundly impact one’s nervous system, eliciting a range of trauma responses. These responses are innate survival mechanisms activated by the body’s stress response system. Recognizing these reactions is crucial for understanding one’s behavior and developing effective coping strategies.

- Fight Response: Confronted with manipulative behaviors from an abusive parent, one may feel compelled to retaliate, either verbally or physically. This can manifest as feelings of anger, frustration, or defiance (“stop it,” “get out of my way”). However, engaging in direct conflict with an abusive parent often exacerbates the situation.

- Flight Response: The unpredictable and hostile environment can induce persistent feelings of anxiety (“something bad is imminent”) or fear (“I’m in danger”). This heightened state may prompt a strong inclination to withdraw, both physically and emotionally. Symptoms may include isolation tendencies, conflict avoidance, or a pervasive sense of unease.

- Freeze Response: In scenarios where escape or confrontation seems unattainable, such as prolonged exposure to abuse, the body may default to a Freeze state. Orchestrated by both the dorsal vagal complex (part of the parasympathetic nervous system) and the sympathetic nervous system, this response can result in dissociation, emotional numbing, or a sensation of being immobilized. This mechanism serves as the body’s adaptive strategy to conserve energy and potentially evade further harm. For survivors of abusive family dynamics, the Freeze response can be a coping mechanism to manage the perpetual threat and unpredictability of the antagonistic caretaker. Nevertheless, unresolved emotions and the incomplete fight-or-flight cycle associated with Freeze can contribute to enduring issues like chronic stress and emotional dysregulation.

- Fawn Response: This response entails engaging in people-pleasing behaviors to mollify the abusive parent and circumvent conflict. It can manifest as over-apologizing, preemptively meeting the abusive parent’s needs, or assuming responsibility for their actions. Although Fawn behavior may appear as a strategy to maintain harmony, it can ultimately perpetuate the power dynamics in the abusive familial relationship.

Understanding and Identifying Your Window of Tolerance

The concept of the “window of tolerance” refers to the optimal zone of arousal where an one functions at their best, both emotionally and cognitively.

Healing from the aftermath of parental narcissism involves a multifaceted journey towards self-awareness, bodily connection, and emotional validation. This journey empowers us to listen to our needs, acknowledge our emotions, set healthy boundaries, and establish a zone of safety for ourselves—free from guilt or shame. This process aligns with our biological imperative for safety and well-being.

The ultimate goal is to activate the “rest and digest” response of the parasympathetic nervous system, commonly known as the ventral vagal state. This state represents our natural equilibrium and safety, fostering an environment where healing and growth can occur.

The ventral vagal state, characterized by feelings of groundedness, mindfulness, joy, curiosity, and overall calmness, serves as our optimal state of social engagement.

The key is to proactively maintain this state and cultivate mindfulness of our nervous system’s transitions between parasympathetic and sympathetic modes. When we detect these shifts, it’s essential to take protective actions to return ourselves to a state of safety. This might involve removing ourselves from triggering situations, practicing calming breathwork during heightened reactivity, or engaging in physical activity when feeling emotionally shut down.

Being mindful of states of overwhelming stress, reactivity, or triggered feelings, as well as the freeze response marked by numbness, hopelessness, or depression, is an important step one must practice when navigating emotional challenges and healing from past traumas. This mindfulness allows for a deeper understanding of our emotional landscape, enabling us to respond rather than react to internal and external triggers.

Describing and labeling these emotional states enables us to deepen our connection with our bodies.

Intense physical and emotional reactions to situations that are disproportionate to the actual threat, or occur in the absence of genuine danger, often signify triggers. While confronting triggers can be uncomfortable, they present opportunities for introspection, allowing us to address past wounds and initiate healing.

Equally vital is recognizing our safe spaces and identifying anchors that brings us genuine joy and comfort. By pinpointing these states and staying attuned to our nervous system’s arousal, we can make decisions that prioritize our well-being. This heightened self-awareness may naturally guide us away from individuals and environments that provoke adverse reactions, ultimately freeing us from the weight of toxic guilt and misplaced responsibility.

Exercises for Nervous System Regulation

Activities to Decrease Nervous System Arousal:

- Deep Breathing: Practice slow and deep diaphragmatic breathing to activate the parasympathetic nervous system.

- Grounding Techniques: Connect with the present moment by focusing on your senses—touch, sight, sound, taste, and smell.

- Progressive Muscle Relaxation (PMR): Systematically tense and then relax different muscle groups to release tension.

- Mindfulness Meditation: Cultivate mindfulness through meditation to bring awareness to the present without judgment.

- Gentle Exercise: Activities like yoga, tai chi or walking in nature.

- Weighted blankets, vests, and pillows: Offers comforting pressure for relaxation.

- Heat: A hot shower, bath or heating pad

- Energy Release Techniques: Shaking, Stomping, Dancing, Singing, lifting weights

Activities to Increase Nervous System Arousal

- Deep Breathing Exercises: Rapid, deep breaths.

- High-Intensity Exercise: Vigorous activities like running or jumping jacks.

- Cold Water Exposure: Splashing cold water on the face or a cold shower.

- Expressive Arts: Engage in creative activities such as drawing, painting, or writing to stimulate the mind.

- Caffeine Intake: In moderation, caffeine can help increase alertness for those with a hypoaroused system.

- Social Connection: Spend time with supportive people to activate the social engagement system.

- Stimulate Senses: Use sensory stimuli like scents, textures, or music to activate sensory pathways.

- Bright Lighting: Exposure to bright, natural light signals wakefulness and boosts alertness.

References

Corrigan, F. M., Fisher, J. J., & Nutt, D. J. (2011). Autonomic dysregulation and the Window of Tolerance model of the effects of complex emotional trauma. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 25(1), 17-25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881109354930

Jabeen, F., Gerritsen, C., & Treur, J. (2021). Healing the next generation: An adaptive agent model for the effects of parental narcissism. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(2), 367-379. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7925789/

The Polyvagal Theory: New Insights into Adaptive Reactions of the Autonomic Nervous System (2009) by Stephen W. Porges: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9131189/

Published on:

THE CONTENTS OF THIS WEBSITE ARE NOT MEANT TO SUBSTITUTE FOR PROFESSIONAL HELP AND COUNSELING. THE READERS ARE DISCOURAGED FROM USING IT FOR DIAGNOSTIC OR THERAPEUTIC ENDS. THE DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OF NARCISSISTIC PERSONALITY DISORDER CAN ONLY BE DONE BY PROFESSIONALS SPECIFICALLY TRAINED AND QUALIFIED TO DO SO. THE AUTHOR IS NOT A MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL. PLEASE CONSULT A HEALTH CARE PROVIDER FOR GUIDANCE SPECIFIC TO YOUR CASE.